03-Application-Architecture FrontEnd 01-Frameworks React

<< ---------------------------------------------------------------- >>

--- Last Modified: $= dv.current().file.mtime

Render Behavior

<< ---------------------------------------------------------------- >>

Render Queue

During the rendering process, React will start at the root of the component tree and loop downwards to find all components that have been flagged as needing updates. For each flagged component, React will call either FunctionComponent(props) (for function components), or classComponentInstance.render() (for class components) , and save the render output for the next steps of the render pass.

After calculating the functions or the render outputs, it diffs it with the previous DOM to see what changes it needs to make so that the DOM has the desired output. This is called “reconciliation”

The React team divides this work into two phases, conceptually:

- The “Render phase” contains all the work of rendering components and calculating changes

- The “Commit phase” is the process of applying those changes to the DOM

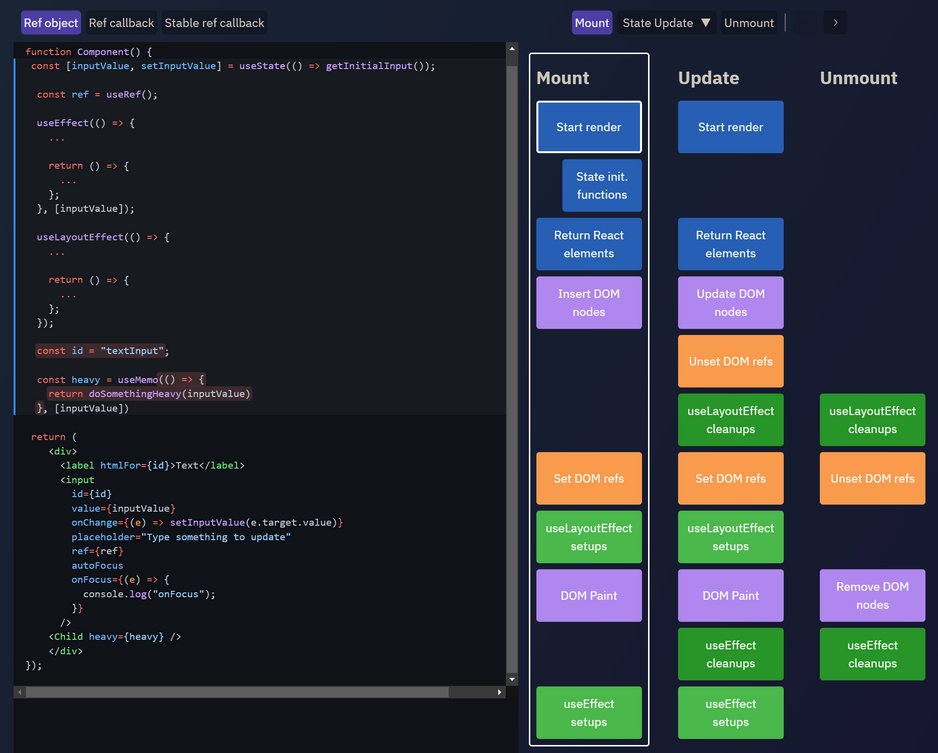

After React has updated the DOM in the commit phase, it updates all refs accordingly to point to the requested DOM nodes and component instances. It then synchronously runs the componentDidMount and componentDidUpdate class lifecycle methods, and the useLayoutEffect hooks.

React then sets a short timeout, and when it expires, runs all the useEffect hooks. This step is also known as the “Passive Effects” phase.

React Fiber Objects

React stores an internal data structure that tracks all the current component instances that exist in the application. The core piece of this data structure is an object called a “fiber”, which contains metadata fields that describe:

- What component type is supposed to be rendered at this point in the component tree

- The current props and state associated with this component

- Pointers to parent, sibling, and child components

- Other internal metadata that React uses to track the rendering process

During a rendering pass, React will iterate over this tree of fiber objects, and construct an updated tree as it calculates the new rendering results.

Note that these “fiber” objects store the real component props and state values. When you use props and state in your components, React is actually giving you access to the values that were stored on the fiber objects. In fact, for class components specifically, React explicitly copies componentInstance.props = newProps over to the component right before rendering it. So, this.props does exist, but it only exists because React copied the reference over from its internal data structures. In that sense, components are sort of a facade over React’s fiber objects.

Similarly, React hooks work because React stores all of the hooks for a component as a linked list attached to that component’s fiber object. When React renders a function component, it gets that linked list of hook description entries from the fiber, and every time you call another hook, it returns the appropriate values that were stored in the hook description object (like the state and dispatch values for useReducer.

When a parent component renders a given child component for the first time, React creates a fiber object to track that “instance” of a component. For class components, it literally calls const instance = new YourComponentType(props) and saves the actual component instance onto the fiber object. For function components, React just calls YourComponentType(props) as a function.

Component Types and Reconciliation

As described in the “Reconciliation” docs page, React tries to be efficient during re-renders, by reusing as much of the existing component tree and DOM structure as possible. If you ask React to render the same type of component or HTML node in the same place in the tree, React will reuse that and just apply updates if appropriate, instead of re-creating it from scratch. That means that React will keep component instances alive as long as you keep asking React to render that component type in the same place. For class components, it actually does use the same actual instance of your component. A function component has no true “instance” the way a class does, but we can think of <MyFunctionComponent /> as representing an “instance” in terms of “a component of this type is being shown here and kept alive”.

So, how does React know when and how the output has actually changed?

React’s rendering logic compares elements based on their type field first, using (===) reference comparisons. If an element in a given spot has changed to a different type, such as going from <div> to <span> or <ComponentA> to <ComponentB>, React will speed up the comparison process by assuming that entire tree has changed. As a result, React will destroy that entire existing component tree section, including all DOM nodes, and recreate it from scratch with new component instances.

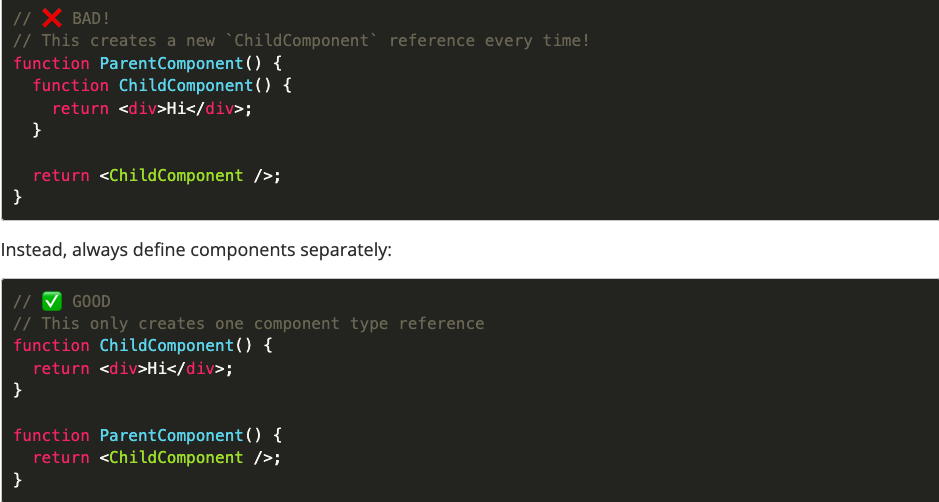

This means that you must never create new component types while rendering! Whenever you create a new component type, it’s a different reference, and that will cause React to repeatedly destroy and recreate the child component tree.

In other words, don’t do this:

Keys and Reconciliation

The other way that React identifies component “instances” is via the key pseudo-prop. React uses key as a unique identifier that it can use to differentiate specific instances of a component type.

Note that key isn’t actually a real prop - it’s an instruction to React. React will always strip that off, and it will never be passed through to the actual component, so you can never have props.key - it will always be undefined.

The main place we use keys is rendering lists. Keys are especially important here if you are rendering data that may be changed in some way, such as reordering, adding, or deleting list entries. It’s particularly important here that keys should be some kind of unique IDs from your data if at all possible - only use array indices as keys as a last resort fallback!

// ✅ Use a data object ID as the key for list items

todos.map((todo) => <TodoListItem key={todo.id} todo={todo} />);Here’s an example of why this matters. Say I render a list of 10 <TodoListItem> components, using array indices as keys. React sees 10 items, with keys of 0..9. Now, if we delete items 6 and 7, and add three new entries at the end, we end up rendering items with keys of 0..10. So, it looks to React like I really just added one new entry at the end because we went from 10 list items to 11. React will happily reuse the existing DOM nodes and component instances. But, that means that we’re probably now rendering <TodoListItem key={6}> with the todo item that was being passed to list item #8. So, the component instance is still alive, but now it’s getting a different data object as a prop than it was previously. This may work, but it may also produce unexpected behavior. Also, React will now have to go apply updates to several of the list items to change the text and other DOM contents, because the existing list items are now having to show different data than before. Those updates really shouldn’t be necessary here, since none of those list items changed.

If instead we were using key={todo.id} for each list item, React will correctly see that we deleted two items and added three new ones. It will destroy the two deleted component instances and their associated DOM, and create three new component instances and their DOM. This is better than having to unnecessarily update the components that didn’t actually change.

Keys are useful for component instance identity beyond lists as well. You can add a key to any React component at any time to indicate its identity, and changing that key will cause React to destroy the old component instance and DOM and create new ones. A common use case for this is a list + details form combination, where the form shows the data for the currently selected list item. Rendering <DetailForm key={selectedItem.id}> will cause React to destroy and re-create the form when the selected item changes, thus avoiding any issues with stale state inside the form.

Render Batching and Timing

By default, each call to setState() causes React to start a new render pass, execute it synchronously, and return. However, React also applies a sort of optimization automatically, in the form of render batching. Render batching is when multiple calls to setState() result in a single render pass being queued and executed, usually on a slight delay.

The React community often describes this as “state updates may be asynchronous”. The new React docs also describe it as “State is a Snapshot”. That’s a reference to this render batching behavior.

In React 17 and earlier, React only did batching in React event handlers such as onClick callbacks. Updates queued outside of event handlers, such as in a setTimeout, after an await, or in a plain JS event handler, were not queued, and would each result in a separate re-render.

However, React 18 now does “automatic batching” of all updates queued in any single event loop tick. This helps cut down on the overall number of renders needed.

Let’s look at a specific example.

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0);

const onClick = async () => {

setCounter(0);

setCounter(1);

const data = await fetchSomeData();

setCounter(2);

setCounter(3);

};With React 17, this executed three render passes. The first pass will batch together setCounter(0) and setCounter(1), because both of them are occurring during the original event handler call stack, and so they’re both occurring inside the unstable_batchedUpdates() call.

However, the call to setCounter(2) is happening after an await. This means the original synchronous call stack is done, and the second half of the function is running much later in a totally separate event loop call stack. Because of that, React will execute an entire render pass synchronously as the last step inside the setCounter(2) call, finish the pass, and return from setCounter(2).

The same thing will then happen for setCounter(3), because it’s also running outside the original event handler, and thus outside the batching.

However, with React 18, this executes two render passes. The first two, setCounter(0) and setCounter(1), are batched together because they’re in one event loop tick. Later, after the await, both setCounter(2) and setCounter(3) are batched together - even though they’re much later, that’s also two state updates queued in the same event loop, so they get batched into a second render.

Async Rendering, Closures, and State Snapshots important

One extremely common mistake we see all the time is when a user sets a new value, then tries to log the existing variable name. However, the original value gets logged, not the updated value.

function MyComponent() {

const [counter, setCounter] = useState(0);

const handleClick = () => {

setCounter(counter + 1);

// ❌ THIS WON'T WORK!

console.log(counter);

// Original value was logged - why is this not updated yet??????

};

}So, why doesn’t this work?

As mentioned above, it’s common for experienced users to say “React state updates are async”. This is sort of true, but there’s a bit more nuance then that, and actually a couple different problems at work here.

Strictly speaking, the React render is literally synchronous - it will be executed in a “microtask” at the very end of this event loop tick. (This is admittedly being pedantic, but the goal of this article is exact details and clarity.) However, yes, from the point of view of that handleClick function, it’s “async” in that you can’t immediately see the results, and the actual update occurs much later than the setCounter() call.

However, there’s a bigger reason why this doesn’t work. The handleClick function is a “closure” - it can only see the values of variables as they existed when the function was defined. In other words, these state variables are a snapshot in time.

Since handleClick was defined during the most recent render of this function component, it can only see the value of counter as it existed during that render pass. When we call setCounter(), it queues up a future render pass, and that future render will have a new counter variable with the new value and a new handleClick function… but this copy of handleClick will never be able to see that new value.

Going back to the original example: trying to use a variable right after you set an updated value is almost always the wrong approach, and suggests you need to rethink how you are trying to use that value.

Render Behavior Edge Cases

Commit Phase Lifecycles

There’s some additional edge cases inside of the commit-phase lifecycle methods: componentDidMount, componentDidUpdate, and useLayoutEffect. These largely exist to allow you to perform additional logic after a render, but before the browser has had a chance to paint todo. In particular, a common use case is:

- Render a component the first time with some partial but incomplete data

- In a commit-phase lifecycle, use refs to measure the real size of the actual DOM nodes in the page

- Set some state in the component based on those measurements

- Immediately re-render with the updated data

In this use case, we don’t want the initial “partial” rendered UI to be visible to the user at all - we only want the “final” UI to show up. Browsers will recalculate the DOM structure as it’s being modified, but they won’t actually paint anything to the screen while a JS script is still executing and blocking the event loop. So, you can perform multiple DOM mutations, like div.innerHTML = "a"; div.innerHTML = b";, and the "a" will never appear.

Because of this, React will always run renders in commit-phase lifecycles synchronously. That way, if you do try to perform an update like that “partial→final” switch, only the “final” content will ever be visible on screen.

As far as I know, state updates in useEffect callbacks are queued up, and flushed at the end of the “Passive Effects” phase once all the useEffect callbacks have completed.

Reconciler Batching Methods

React reconcilers (ReactDOM, React Native) have methods to alter render batching.

For React 17 and earlier, you can wrap multiple updates that are outside of event handlers in unstable_batchedUpdates() to batch them together. (Note that despite the unstable_ prefix, it’s heavily used and depended on by code at Facebook and public libraries - React-Redux v7 used unstable_batchedUpdates internally)

Since React 18 automatically batches by default, React 18 has a flushSync() API that you can use to force immediate renders and opt out of automatic batching.

Note that since these are reconciler-specific APIs, alternate reconcilers like react-three-fiber and ink may not have them exposed. Check the API declarations or implementation details to see what’s available.

Setting States During Render

However, there is one exception to this. Function components may call setSomeState() directly while rendering, as long as it’s done conditionally and isn’t going to execute every time this component renders. This acts as the function component equivalent of getDerivedStateFromProps in class components. If a function component queues a state update while rendering, React will immediately apply the state update and synchronously re-render that one component before moving onwards. If the component infinitely keeps queueing state updates and forcing React to re-render it, React will break the loop after a set number of retries and throw an error (currently 50 attempts). This technique can be used to immediately force an update to a state value based on a prop change, without requiring a re-render + a call to setSomeState() inside of a useEffect.

Improving React Render Performance

Three main APIs to optimize react performance

- The primary method is

React.memo(), a built-in “higher order component” type. It accepts your own component type as an argument, and returns a new wrapper component. The wrapper component’s default behavior is to check to see if any of the props have changed, and if not, prevent a re-render. Both function components and class components can be wrapped usingReact.memo(). (A custom comparison callback may be passed in, but it really can only compare the old and new props anyway, so the main use case for a custom compare callback would be only comparing specific props fields instead of all of them.) - There’s also a lesser-known technique as well: if a React component returns the exact same element reference in its render output as it did the last time, React will skip re-rendering that particular child. There’s at least a couple ways to implement this technique:

- If you include

props.childrenin your output, that element is the same if this component does a state update - If you wrap some elements with

useMemo(), those will stay the same until the dependencies change

- If you include

Immutability and Rerendering

State updates in React should always be done immutably. There are two main reasons why:

- depending on what you mutate and where, it can result in components not rendering when you expected they would render

- it causes confusion about when and why data actually got updated

Let’s look at a couple specific examples.

As we’ve seen, React.memo / PureComponent / shouldComponentUpdate all rely on shallow equality checks of the current props vs the previous props. So, the expectation is that we can know if a prop is a new value, by doing props.someValue !== prevProps.someValue.

If you mutate, then someValue is the same reference, and those components will assume nothing has changed.

Note that this is specifically when we’re trying to optimize performance by avoiding unnecessary re-renders. A render is “unnecessary” or “wasted” if the props haven’t changed. If you mutate, the component may wrongly think nothing has changed, and then you wonder why the component didn’t re-render.

Context and Rendering Behavior

In this example, every time ParentComponent renders, React will take note that MyContext.Provider has been given a new value, and look for components that consume MyContext as it continues looping downwards. When a context provider has a new value, every nested component that consumes that context will be forced to re-render.

Note that from React’s perspective, each context provider only has a single value - doesn’t matter whether that’s an object, array, or a primitive, it’s just one context value. Currently, there is no way for a component that consumes a context to skip updates caused by new context values, even if it only cares about part of a new value.

It’s time to put some of these pieces together. We know that:

- Calling

setState()queues a render of that component - React recursively renders nested components by default

- Context providers are given a value by the component that renders them

- That value normally comes from that parent component’s state

This means that by default, any state update to a parent component that renders a context provider will cause all of its descendants to re-render anyway, regardless of whether they read the context value or not!.

optimization example:

function GreatGrandchildComponent() {

return <div>Hi</div>

}

function GrandchildComponent() {

const value = useContext(MyContext);

return (

<div>

{value.a}

<GreatGrandchildComponent />

</div>

}

function ChildComponent() {

return <GrandchildComponent />

}

const MemoizedChildComponent = React.memo(ChildComponent);

function ParentComponent() {

const [a, setA] = useState(0);

const [b, setB] = useState("text");

const contextValue = {a, b};

return (

<MyContext.Provider value={contextValue}>

<MemoizedChildComponent />

</MyContext.Provider>

)

}Now, if we call setA(42):

ParentComponentwill render- A new

contextValuereference is created - React sees that

MyContext.Providerhas a new context value, and thus any consumers ofMyContextneed to be updated - React will try to render

MemoizedChildComponent, but see that it’s wrapped inReact.memo(). There are no props being passed at all, so the props have not actually changed. React will skip renderingChildComponententirely. - However, there was an update to

MyContext.Provider, so there may be components further down that need to know about that. - React continues downwards and reaches

GrandchildComponent. It sees thatMyContextis read byGrandchildComponent, and thus it should re-render because there’s a new context value. React goes ahead and re-rendersGrandchildComponent, specifically because of the context change. - Because

GrandchildComponentdid render, React then keeps on going and also renders whatever’s inside of it. So, React will also re-renderGreatGrandchildComponent.

React-Redux Rendering Behavior

I’ve seen a lot of folks repeat the phrase “React-Redux uses context inside.” Also technically true, but React-Redux uses context to pass the Redux store instance, not the current state value. That means that we always pass the same context value into our <ReactReduxContext.Provider> over time.

Remember that a Redux store runs all its subscriber notification callbacks whenever an action is dispatched. UI layers that need to use Redux always subscribe to the Redux store, read the latest state in their subscriber callbacks, diff the values, and force a re-render if the relevant data has changed. The subscription callback process happens outside of React entirely, and React only gets involved if React-Redux knows that the data needed by a specific React component has changed (based on the return values of mapState or useSelector).

This results in a very different set of performance characteristics than context. Yes, it’s likely that fewer components will be rendering all the time, but React-Redux will always have to run the mapState/useSelector functions for the entire component tree every time the store state is updated. Most of the time, the cost of running those selectors is less than the cost of React doing another render pass, so it’s usually a net win, but it is work that has to be done. However, if those selectors are doing expensive transformations or accidentally returning new values when they shouldn’t, that can slow things down.